After the Treaty of London in 1867, the fortress of Luxembourg was dismantled. The fortifications were demilitarised, defunctionalised, blown up, demolished and filled in. Some parts, however, have been preserved. These remnants of the fortress, many of which are now underground, are known in Luxembourg as “casemates”.

While the term usually refers to a room equipped for artillery, the local understanding of “casemates” includes all the underground remains of the fortress – mostly a large maze of corridors – that span (almost) the entire capital, covering more than 10 km. There is no up-to-date, reliable documentation of this hidden part of the fortress, however, apart from historical and more recent maps and plans. Technology offers a way forward, allowing us to document existing structures accurately, to publish them online and to contextualise them.

Boulevard Royal/Avenue Amélie built on the dismantled fort Marie and arsenal complex

POV: Musée Dräi Eechelen – How the project started

In 2018, as part of the “Année du Patrimoine”, the Centre de documentation sur la forteresse de Luxembourg (CDF) developed the guided tour “À l’assaut du Kirchberg” (still running!) and made a series of 3D scans of the casemates and galleries of Fort Thüngen, home to the Musée Dräi Eechelen, as well as of Fort Olizy and Fort Niedergrünewald, which also feature in the tour. After this first foray into 3D scanning, the CDF teamed up with the MNAHA’s digital department, venturing not only extra muros, but sub muros as well.

We decided to scan further casemates two different ways. We first scanned them using Matterport, which is readily accessible and easy for users to navigate. It’s what we used to scan Forts Thüngen, Olizy and Niedergrünewald. Unfortunately, Matterport is a proprietary format that does not allow for long-term archiving. This can lead to catastrophic results: a detailed 3D Matterport scan of the fortress of Komárno in Slovakia, for example, is no longer available.

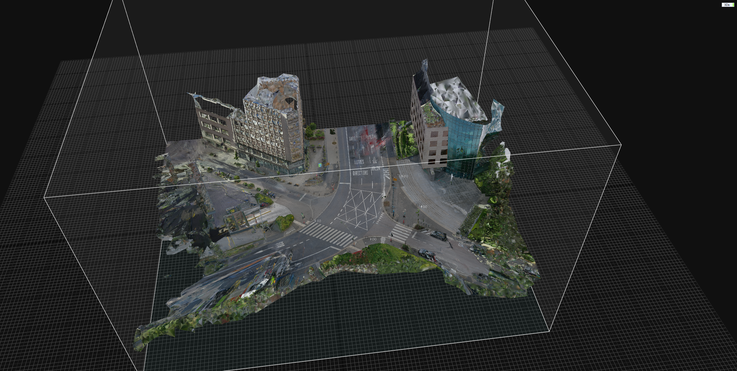

We also did a photogrammetric laser scan, which consists of several thousands of photographic images that can be georeferenced and archived. This method is both more intricate and complex than Matterport, which is why it takes significantly more time and resources. The resulting scan is a lot more detailed and offers a long-term solution for documenting the remains of the fortress. It can also be used by engineering offices and surveyors in addition to skilled users.

Which casemates have been scanned, exactly?

We decided to document the coherent network of casemates below the municipal park. Designed by Edouard André (1840-1911), with its green spaces interspersed with promenades, the park was built on the remains and foundations of the fortifications that protected the city to the north-west.

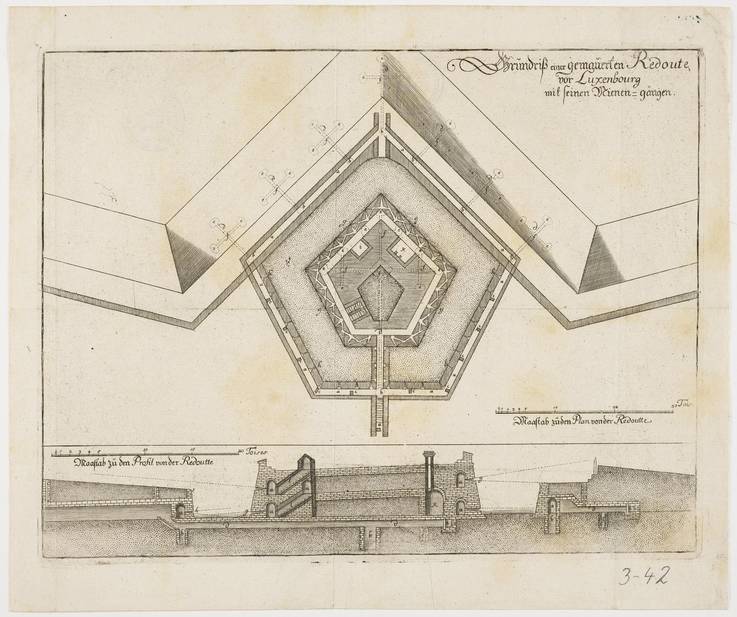

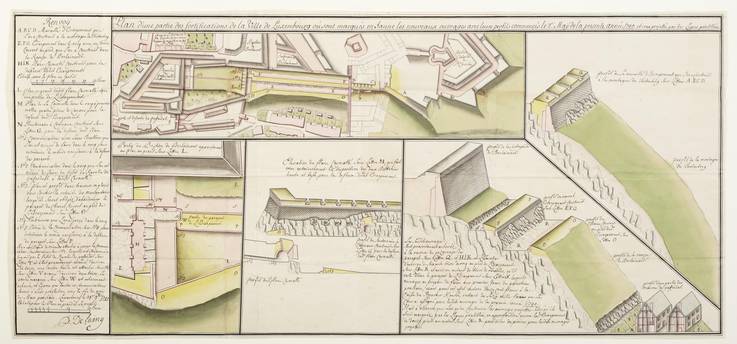

The engineer and later commander Jean-Chrétien Charles de Landas de Louvigny (?-1691) had the fortress reinforced on this front starting in 1672 and built new, low, pentagonal towers (redoubts) surrounded by a deep moat: the Peter, Louvigny, Marie and Berlaymont redoubts. After Louis XIV’s troops took over the town in 1684, Sébastien Le Prestre de Vauban (1633-1707) had three more redoubts built between the existing ones: the Lambert, Vauban and Royal redoubts. This architecture subsequently set a precedent: Vauban had towers like those built in fortresses across the entire realm of the Sun King.

As part of the building projects of the Austrian Habsburgs under the direction of the engineer Simon de Bauffe, these redoubts were reinforced in the 1730s with an envelope, a defensive structure built around the redoubts. A century later, they were modernised again under the Prussian governance of the federal fortress. Unforeseeable at the time, the razing of the fortress from 1867 meant the redoubts were buried under a planted area, which André turned into a municipal park. Before the outbreak of the Second World War, the historian Jean-Pierre Koltz (1909-1989) presented a project to convert some of the casemates into air raid shelters, which was carried out in 1939 and 1940.

Built under the Spanish Habsburgs, extended by the French crown, reinforced by the Austrian Habsburgs, modernised by the German Confederation and repurposed during the Second World War, the casemates in and under the municipal park bear witness to significant events throughout modern and contemporary history.

The Europeana Twin It! Campaign

In the first months of 2024 the Casemates 3D project was selected by Luxembourg’s Ministry of Culture to be part of the Europe-wide Twin it! campaign organised by the European Union. Each member state was invited to share one 3D digitised object – anything from a sculpture to a building – that is either cultural heritage at risk, a key object for the country’s cultural heritage or a type of cultural heritage that has not been 3D digitised often. The aim was not only to collect some of the most interesting objects Europe has to offer, but also to encourage all member states to experiment with 3D and to build skills in this area.

Our participation in this campaign means that the casemates below Villa Louvigny are one of the first 3D digitised objects to be published on Europeana’s platform by Luxembourg. It has also pushed us to publish a first version of what over time is going to become an in-depth study of Luxembourg’s casemates.

Philippe Delaing, The fortifications of Tintenberg, after 1739.

Casemates 3D on MNAHA Collections

At first glance, the 3D model published on Europeana is reminiscent of a video game level design – long outstretched tunnels that you can imagine getting lost in, with nothing above or around them. Yet it is a very real place that was built for a specific purpose at a particular moment in history. This requires explanation, which is why we created a special page on MNAHA Collections (collections.mnaha. lu) to put the 3D casemates models into context. Here, we showcase the models of all the forts that we were able to scan so far and provide information on their history, location, and purpose by connecting them with each other and to other objects in the CDF’s museum collections. We will continually keep adding information and links to additional objects as we continue to publish the models on the platform.

What's next?

In addition to adding further information about the casemates that have already been scanned to MNAHA Collections, scanning more elements of Luxembourg’s fortress is a tempting prospect. The existing models not only invite further study of how they worked in the past, but hopefully can also be part of a discourse on how to preserve such architectural features in the future.

While creating more models is dependent on the allocation of the necessary resources, this project allowed us to learn more about the different possibilities that exist in the realm of 3D scanning cultural heritage and how to make it accessible. Doing it in a way that the data can be preserved in the long term is currently still very labour-intensive and requires an advanced digital set-up not only to store the data but to make the models accessible to a larger public. In any case, this project shows that there is a need for further research. There is an opportunity here to combine resources from different departments – the CDF for their in-depth knowledge of the history of the casemates and the digitalisation department of the MNAHA for their expertise in storing, handling and publishing digital objects – and to work with institutions that have expertise in creating, maintaining, preserving and using 3D models.

Authors: Edurne Kugeler and Ralph Lange - Images: invisible.lu / MNAHA Collection

Source: MuseoMag N°III 2024