In 1963, Francis Bacon met George Dyer, his greatest muse and lover. Their first encounter is shrouded in myth. Some say Dyer, a small-time thief from London’s East End, was caught breaking into Bacon’s studio in London. Bacon himself claims that the pair met in a bar in Soho. Either way, it was the start of an intense and complicated relationship that lasted almost a decade, ending abruptly with Dyer’s suicide in 1971. Overwhelmed with grief, Bacon continued to paint Dyer after his tragic death; indeed, his lover appeared in more than 40 paintings throughout his career.

We are lucky enough to have Bacon’s very first portrait of Dyer on display at our museum for the next two years. This triptych is also the first work of art to be listed on ARTEX Global Markets, a trading venue that aims to democratise investment in art. Painted just a few months after they first met, Three Studies for Portrait of George Dyer (1963) depicts Dyer in pink and turquoise undertones, the face distorted in the artist’s signature style which draws on the aesthetics of flesh and meat, peeling away the skin to expose the tortured psyche beneath. The violence of the rendering is palpable, as is the sense of fervent devotion, evident in the triptych format traditionally used in religious worship. This simultaneous sense of rage and passion is typical of Bacon’s portrayal of his lover, whom he painted obsessively over the following years. To mark the arrival of the very first portrait of George Dyer at the museum, we take a moment to consider the tumultuous love affairs that shaped Bacon’s life and work.

Francis Bacon (1909-1992), Three Studies for Portrait of George Dyer, 1963, oil on canvas, in three parts, 35.5 x 30.5 cm (each). The first publicly listed Masterpiece on Artex Global Markets. Owned by Art Share 002 © The Estate of Francis Bacon. All rights reserved, DACS 2024 / Photo: Tom Lucas / MNAHA

Peter Lacy: The abusive fighter pilot

Turbulent relationships with complex, difficult men were a recurring feature in Bacon’s love life and left an indelible mark on his work. Before he met Dyer, Bacon was romantically involved with Peter Lacy, often portrayed as a fighter pilot and abusive drunk. They first met a private members’ club in Soho in 1952 and started an on-and-off relationship marked by passion, but also violence, until Lacy’s death in 1962. It is said that Lacy once threw Bacon through a window in a fit of passion, and the pair were known to engage in brutal yet consensual S&M practices. Bacon once said: “I couldn’t live with him, and I couldn’t live without him.” Lacy heavily featured in the artist’s work, often serving as the model for male figures and at times explicitly named in the titles.

Study for Portrait of P.L. No. 2 from 1957, for instance, depicts a naked Lacy confidently lounging on a dark, hard-edged sofa, the background more suggested than sketched in any detail. His gaze is watchful, almost menacing, and his erect penis visible, though partially obscured by the dark undertones of the lower half of the canvas. The painting is an exploration of the physicality of the male body, one that Bacon would paint over and over again. “Being in love in that way, being absolutely physically obsessed by someone, is like an illness,” the artist noted in a conversation with his biographer Michael Peppiatt, underlining the compulsive, almost toxic, nature of their relationship.

Lacy’s death in Tangier had a profound impact on Bacon, who produced a number of works in memory of his lover, including Landscape near Malabata, Tangier (1963), a charged, whirling depiction of anger and pain set in the city Lacy had made his home, and Study for Three Heads (1962), which bears a striking resemblance to the portrait of Dyer painted a year later. The latter marked the end of one era and the beginning of the next.

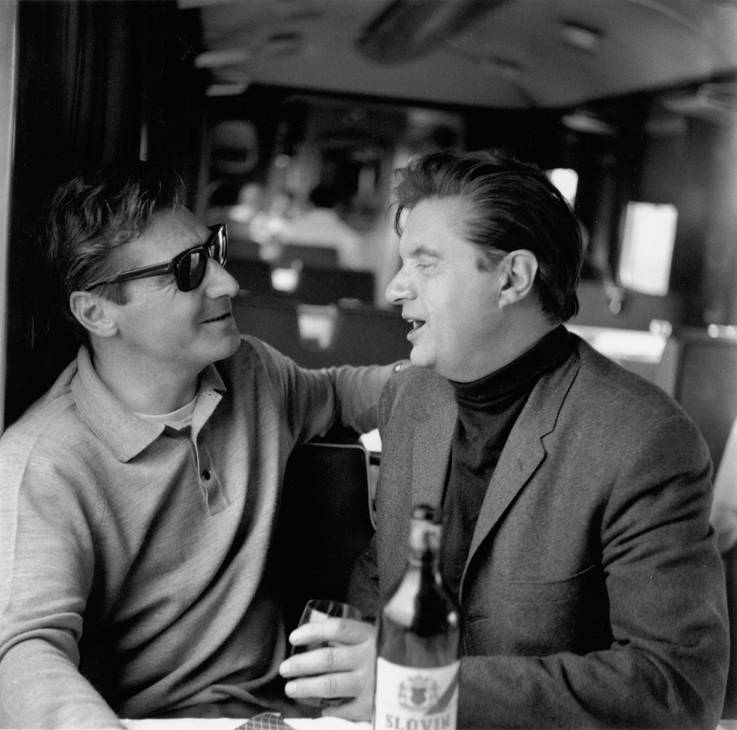

John Deakin, Francis Bacon and George Dyer on the Orient Express to Athens, 1965, Gelatin silver print, 19 x 19cm © The Estate of Francis Bacon. All rights reserved, DACS/Artimage 2021. Photo: John Deakin

George Dyer: The East End criminal

Bacon’s affair with Dyer was equally tempestuous; Dyer was said to be mercurial, aggressive and prone to depression and addiction, increasingly so over their decade-long relationship. Their intense relationship fuelled Bacon’s creative practice, yet it was perhaps his overdose-induced suicide in the pair’s hotel room in Paris just days before Bacon’s retrospective at the Grand Palais that marked his work the most. Haunted by the spectre of his lover, Bacon’s so-called Black Triptychs stage different phases of Dyer’s death in non-chronological order, with portrayals of him in the hotel room and hunched over the toilet, punctuated by ominous shadows and single bare lightbulb, the artist processing his grief in compulsive reenactments and retellings of his lover’s suicide.

In an interview shortly after Dyer’s death, Bacon noted; “People say you forget about death, but you don’t. After all, I’ve had a very unfortunate life, because all the people I’ve been really fond of have died. And you don’t stop thinking about them; time doesn’t heal. But you concentrate on something which was an obsession, and what you would have put into your obsession with the physical act you put into your work.” Both with Lacy and Dyer, we see the artist visiting and revisiting their face and form obsessively, contorting them almost beyond recognition in a visceral act of memorialisation.

It is interesting to consider Czech writer Milan Kundera’s observation here; “Bacon’s portraits are a question about the limits of the self. To what degree of distortion does an individual still remain himself?” This constant renegotiation of the boundary between the self and other is an intriguing aspect of Bacon’s work; by appropriating his lovers’ physical features and very identity by painterly means, they become an extension of his own psyche. Thus, when we look at a work like Three Studies for Portrait of George Dyer, we see both Dyer and Bacon staring back at us, flickering between the two intermittently. This complex oscillation between the self and other is perhaps part of the reason why Bacon’s renderings of his lovers have produced some of the most powerful images in his oeuvre.

View of the exhibition “Francis Bacon: The Beauty of Meat”, 2024 - Photo: Eduardo Ortega. Acervo do [Collection of] Centro de Pesquisa do [Reserach Center of] Museu de Arte de São Paulo Assis Chateaubriand © The Estate of Francis Bacon. All rights reserved, DACS 2024, Photo: Eduardo Ortega / MASP

Queering Bacon: New perspectives

Though queer might not have been the word that Bacon used to describe his identity, he has been referred to and reclaimed as such by recent critics and exhibitions because of his bold depictions of queer love at a time when sexual acts between men were, for the most part, still against the law in the UK. The 2017 show Queer British Art 1861–1967 at Tate Britain, London, dedicated a whole room to Bacon’s fearless portrayals of same-sex desire alongside the work of David Hockney whilst the 2024 show Francis Bacon: The Beauty of the Meat at MASP, São Paolo, was the first exhibition to focus on queer aspects of the artist’s personal life and artistic production – a perspective that has been overlooked in Bacon scholarship thus far. This growing recognition invites further exploration of Bacon’s legacy as a queer artist, ahead of his time in both his work and his life.

Bacon’s Three Studies for Portrait of George Dyer is on display in the museum’s permanent exhibition of modern and contemporary art, which is free to visit. Free guided tours of the artwork will be on offer every Tuesday in October at 12:30 pm and on Wednesday 13 November at 3 pm. Theatre director Thierry Mousset will also present a performance inspired by Bacon’s triptych at Nuit des Musées on 12 October 2024.

Text: Katja Taylor - Photos: John Deakin / Eduardo Ortega / MASP; Tom Lucas / MNAHA | © The Estate of Francis Bacon. All rights reserved, DACS 2024

Source: MuseoMag N°IV 2024