We are lucky enough to have a triptych by Francis Bacon at the museum for the next year and a half thanks to a loan managed by ARTEX Global Markets, a stock exchange that aims to democratise investment in art.

Three Studies for Portrait of George Dyer (1963) portrays the artist’s lover George Dyer and gives us the occasion to explore different facets of Bacon’s life and work. In the last issue of the MuseoMag, we explored the tumultuous love affairs that shaped the artist both privately and professionally.

This time, we turn more specifically to how Bacon paved the way for expressions of queerness in Western visual culture. Increasingly, the Bacon’s work is being examined through the lens of queer identity. Yet to fully understand this aspect of his oeuvre, we must first consider his trajectory as an artist and the sociopolitical context in which he lived and worked, after which we can move on to explore how he responded to this world in his art, specifically in a number of works ostensibly depicting a pair of wrestlers.

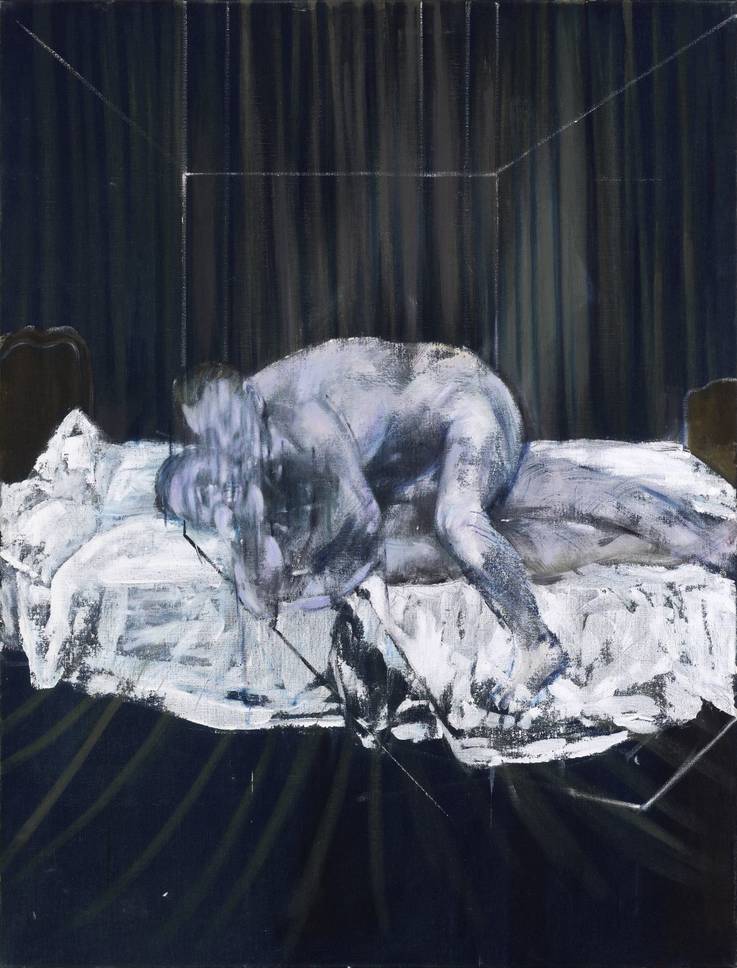

Francis Bacon, Two Figures, 1953, oil on canvas, 152.5 x 116.5cm, private collection. © The Estate of Francis Bacon. All rights reserved, DACS/Artimage. Photo: Prudence Cuming Associates Ltd

Being queer in Britain

Born in Ireland in 1909, Bacon had a complicated relationship with his family due to his emerging homosexuality and was thrown out of the family home at the age of 16, allegedly for wearing his mother’s underwear. After a brief stint in London, Berlin and France, where his interest in fine art was sparked, he moved back to London in 1929 to pursue a career as a designer. He quickly gave up on this career path and focused on painting instead. Bacon’s early successes came in the 1930s with his inclusion in several group shows, but 1948 marked a turning point in his career, when his Painting 1946 was acquired by the Museum of Modern Art, New York.

In the 1950s, Bacon established himself as one of Britain’s leading post-war painters, exhibiting internationally at important venues. The 1960s was the most important decade in Bacon’s career, with his first major museum retrospective at the Tate Gallery in London in 1962. By the time he exhibited there again, in 1985, the then-director of the Tate, Sir Alan Bowness, hailed him as “the greatest of living painters”. Seven years later, he passed away in Madrid at the age of 82.

Over the course of Francis Bacon’s lifetime, rights for queer people in Britain changed dramatically. In the year of his birth in 1909, male homosexual acts were illegal and punishable by imprisonment, and Oscar Wilde’s famous 1895 trials for “gross indecency” were still in living memory. When Bacon started to gain critical acclaim in London in the early 1950s, there was a particularly harsh crack-down on sexual behaviour between men by the police. In 1952 alone, there were 670 prosecutions for sodomy, 3087 for attempted sodomy and indecent assault and 1686 prosecutions for gross indecency.

One of the most high-profile cases involved Alan Turing, a well-known mathematician and World War II code breaker. Turing was convicted in 1952 and forced to undergo chemical castration, a type of hormone treatment designed to reduce the libido of sex offenders. He took his own life two years later. Another case splashed across the national press was the arrest and fining of the recently knighted actor Sir John Gielgud in 1953, followed by the scandalous trial of Lord Montagu, Michael Pitt-Rivers and Peter Wildeblood the year after. This was the context in which Bacon was living and working; a dangerous time to be queer, with the very real threat of being convicted if caught.

1967, however, marked a turning point in the history of queer rights in Britain, when homosexual acts were partially decriminalised in the Sexual Offences Act. Though bans on buggery and indecency between men were still in force, homosexual acts were legal if they were consensual, took place in private and both parties were over the age of 21. This would have allowed Bacon to live more freely, though queer relationships were still very much relegated to the private space. Significant change in terms of queer rights would only come many years later with the passing of the Equality Act 2010, which offered protection from discrimination based on sexual orientation.

Francis Bacon, Two Figures in the Grass, 1954, oil on canvas, 152 x 117 cm, private collection. © The Estate of Francis Bacon. All rights reserved, DACS/Artimage. Photo: Prudence Cuming Associates Ltd

Wrestlers or lovers?

Under the threat of strict laws surrounding his sexual practices for most of his life, Bacon still managed to be “the loudest, rudest, drunkest, most sought-after British artist of the 20th century”, as the BBC documentary A Brush with Violence (2017) put it. Indeed, Bacon lived decadently and excessively, frequenting establishments ranging from grand hotels and fancy restaurants to disreputable clubs and gambling joints in London’s seedy underbelly – a lifestyle his biographer Daniel Farson describes as a “gilded gutter life”. How did Bacon reconcile being in the limelight with his love affairs that until 1967 were considered illegal and even after that had to be conducted behind closed doors?

This tension between the public and the private is evident in Bacon’s portrayals of wrestlers from the early 1950s. Two Figures (1953) depicts two naked men grappling with each other, which could either be read as wrestling or a sexual act. Here, the artist draws on the compositions of Eadweard J. Muybridge’s photographs of wrestlers from the late 19th century, a historical reference that in some sense legitimises the scene by setting a precedent. However, while Muybridge portrays his wrestlers outside, Bacon situates them in a closed, windowless room on a disheveled bed. We as viewers are placed by the door and take on the role of voyeurs witnessing a private sexual act. Treading a fine line between athletic portrayals and erotic imagery, this provocative painting draws attention to the open secret of same-sex relations, forging a space where this is tacitly acknowledged and on public display in art galleries.

Similarly, Bacon’s Two Figures in the Grass (1954), which was painted the following year, portrays two naked men entwined on a stretch of grass – more public, certainly, yet still enclosed on all sides by a fence, the corrugated metal reminiscent of the veil-like elements in Two Figures. We as the audience seem to peer over the fence, depicted as a wide black band of paint that takes up the lower quarter of the canvas, again caught in a voyeuristic act. Here, the artist seems to allude to the practice of cruising, where gay men in search of anonymous, casual sex would meet in backstreets or public parks and engage in covert sexual acts. Hidden yet not hidden, Bacon’s coded imagery creates liminal spaces of freedom in a restrictive society and engages with the notion of queer selfhood in complex ways, building up a queer visual vocabulary all while being policed by gallerists and museums.

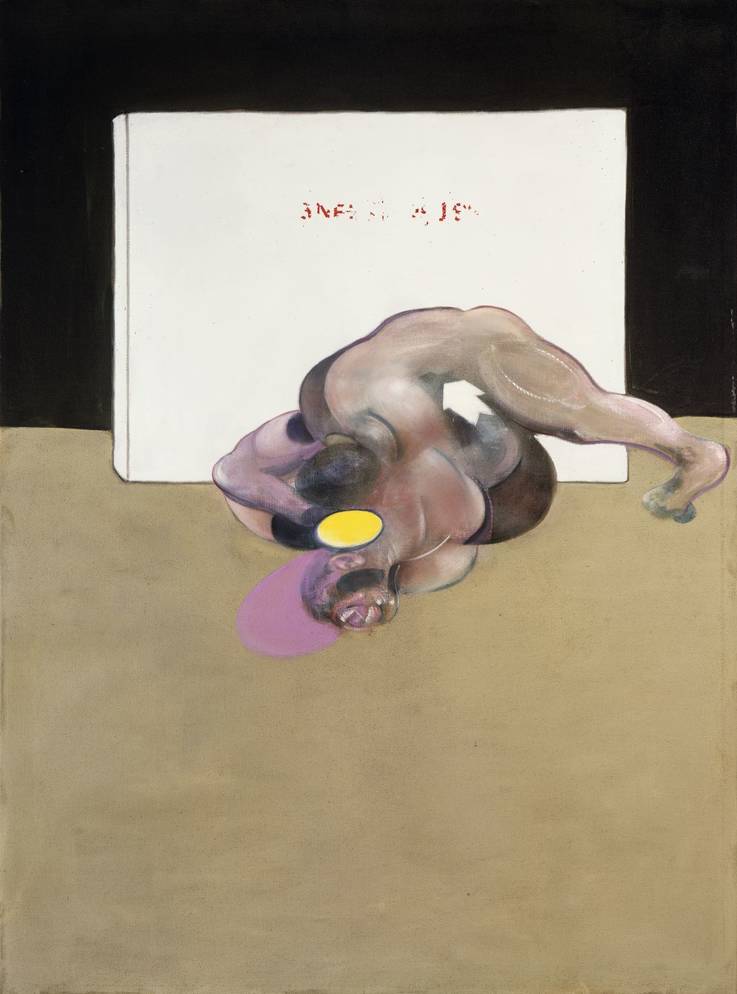

It is interesting to note that Bacon returned to the motif of the wrestlers later on in his career. The Wrestlers after Muybridge (1980) explicitly references his purported original source, yet is a real departure in terms of style, the entangled men rendered much more minimally than in his works from the early 1950s. The upper figure’s detached left arm resembles that of a mannequin with hollows at the wrist and shoulder joints, whilst the lower figure’s facial features are reduced to an ear and an open mouth with visible teeth. The colour palette, too, is very different from the sombre tones of the earlier works, with hot pink and bright yellow accents. Bacon’s figures appear to grapple in a white cube gallery. The red writing on the wall behind them has been all but erased, underscoring the ambiguity of the painting where something is simultaneously visible and invisible, partially erased yet still recognisable. In this evolution of the wrestling motif, however, Bacon’s subjects seem to have moved out of the shadows of covert intimacy to claim a more public space, heralding a shift in the representation of queer relationships in art.

Francis Bacon, The Wrestlers after Muybridge, 1980, oil, aerosol paint and dry transfer lettering on canvas, Frederick R. Weisman Art Foundation, Los Angeles. © The Estate of Francis Bacon. All rights reserved, DACS/Artimage. Photo: Prudence Cuming Associates Ltd

A queer visual vocabulary

Bacon’s work not only reflected his personal experiences and the challenges of his time but also pushed the boundaries of what could be publicly explored in art. By portraying intimate and coded depictions of queerness, he carved out a space for defiance within a largely hostile societal framework. His art invites us to consider how visual culture can challenge norms, making his practice as powerful today as it was provocative in his lifetime.

Text: Katja Taylor

Source: MuseoMag N° I - 2025

Visit the museum’s modern and contemporary art section to see Francis Bacon’s depiction of queer love in his stunning triptych Three Studies for Portrait of George Dyer (1963). This display is free to visit at any time.

Join cultural critic Vera Herold for a free guided tour about queer aspects of Bacon‘s practice on 13 March at 6 pm.

Join art historian Nathalie Becker for a free guided tour exploring the concept of the sacred in Bacon’s work on 27 March at 6 pm.